Why You Should Travel To Sumba, Indonesia

Unbridled. Unsaddled. Barefoot and at full gallop. After a few days of languid indulgence on the resort grounds, this thundering run is jarring me awake to my surroundings. Awake to Sumba. The real Sumba. The one I'd nearly forgotten. Sumba is one of the poorest places on Earth. Downtrodden and diseased. Ancient tribes battling with swords and spears on horseback. Animal sacrifices. Megalithic burials. Stone Age culture. It's beautiful and barbaric. Yet here we sip lychee martinis on the porch. Eat crab cakes and chocolate mousse on a perch overlooking our private surf break. Jet Skis and infinity pools. Pedicures and warm cookies. But the maddest part of this whole lavish sacrilege is that it's entirely humanitarian. With each oyster shooter, I am saving children. With each in-room massage, I diminish the burden of impoverished families. I'm building bridges, curing disease and easing the suffering of an entire culture. And it feels so good. Clinging desperately to the horse beneath me, I am actually saving Sumba. If I can only survive this ride."We're running this entire place on coconuts." Claude Graves is a man of vision. He waves a hand at the resort he founded, Nihiwatu, which blends into the scenery. "Sure, I could be buying diesel at half the price, but that's not the point."

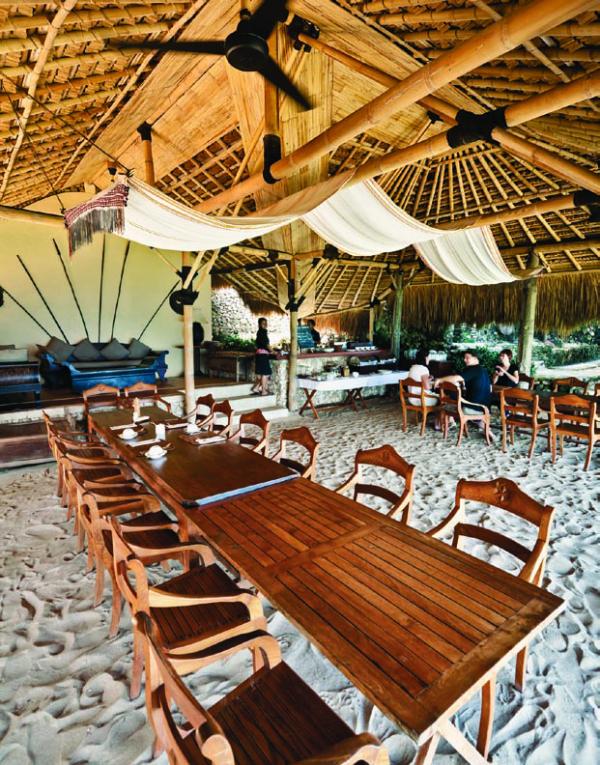

Locals harvest the coconuts. The Sumba Foundation turns them into bio-diesel. The resort buys the power. Guests get all-night air conditioning and a thumping sound system. Locals get a decent wage. Everybody benefits. And that is the point — which pretty well sums up Nihiwatu. Despite fivestar luxury, everything reciprocates with the local culture. Not that you'd notice. Lounging beside the pool. Strolling the ivory beaches. Reeling in a marlin or trading set waves. The Nihiwatu experience short-circuits notions of electricity altogether. Candles and bonfires replace flat-screens and Wi-Fi. Subtle lighting and AC barely disrupt the starlight and ocean breeze. Tranquility so absolute that ...

Claude is about to say more, but he stops. He's not boastful, but he is passionate. Nihiwatu isn't just his resort. It's his life. His gift. To his guest and to this Indonesian island. And we're peeling off the wrapping one piña colada at a time. Sunset is fading. The night's first pinholes pierce the sky. Second piña coladas slide down the bar. A bonfire blazes on the grassy bluff as surfers hunt a final ride. Our group includes a billionaire investment banker, a Hollywood actor, a honeymooning shoe designer and a pair of surf-bumming real-estate developers. Everyone has a story, but all eyes land on our host as he recounts Nihiwatu's rough-hewn origin.

A Jersey-grown surfer, Claude walked a traveler's life — building oil rigs in Java, pioneering Bali in the '70s, running a nightclub in Kenya, living as a ski bum in Seattle. In the mid-'80s, he and his wife, Petra, set out with a pair of around-the-world tickets and a lofty dream for a surf resort where women don't wind up widowed on the beach. A native experience where culture isn't trampled. An "eco-resort" before such a term existed.

"We had this whole list of requirements," Claude explains. "Remote and secluded. Primitive culture. Perfect sand."

On cue, everyone checks the sandy floor. It's pure white, but not too fine, not too coarse. Silky but not squeaky.

"We took samples everywhere," he says. "I still have all the vials. Nihiwatu has the most perfect sand in the world."

Philippines, Africa, Indonesia — Claude and Petra were touring coastlines on the moon. In each locale they'd hire guides, take buses, hike in, camp out — whatever it took, and more, to reach the unreachable. When their path fell into the sea, Claude would paddle out with a surfboard and mask to explore the reefs and sample the waves.

In those days, just getting to Sumba, tucked in the Lesser Sunda Islands, was an adventure. By bus and then on foot, Claude and Petra wandered remote and untested regions populated by fierce tribes. On their second Sumba trip, they found this bay. Perfect waves. Perfect sand. Their holy grail. And then it got really tough. They built roads. They wooed local government. They evolved from a few workers to a staff of 300. Founding Nihiwatu became their lives. Robinson Crusoe meets Frank Lloyd Wright. It took 10 years before Nihiwatu was ready to open in

1996, only to see everything destroyed by a massive 7.0 earthquake. Then came an Asian economic crisis. Another four years passed before Nihiwatu would open.

Malaria? "I stopped counting after the 36th time."

Wildlife? "Petra once climbed into a drainpipe to remove a 5-meter python clogging the system."

Life changes? "Our daughter Gina was born while we were building this place — the Sumbanese gave her a royal name. She loves all animals and refused to bathe without one. Today she rides horses even the locals refuse to mount."

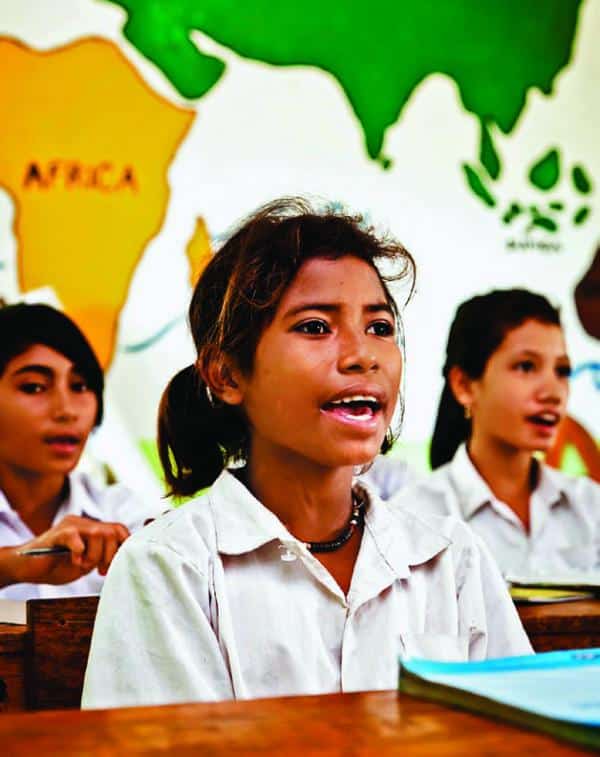

After the family spent years just trying to survive, Gina rekindled her parents' original vision. Claude set up a play group for Gina and was shocked at the contrast between his daughter and the local children.

"Here was Gina crawling around looking robust and full of life, while her playmates appeared nearly dead. The youngest could not lift their heads, and the parents weren't looking so good either."

Soon after, Claude mentioned his new plan to a friend.

"I'm creating something called the Sumba Foundation," he said. "I'm going to devote my life to it."

Now Claude turns to me, the nonbillionaire journalist. He wants me to see for myself.

"You should have Dato take you up to his village," he says. "See what's really going on."

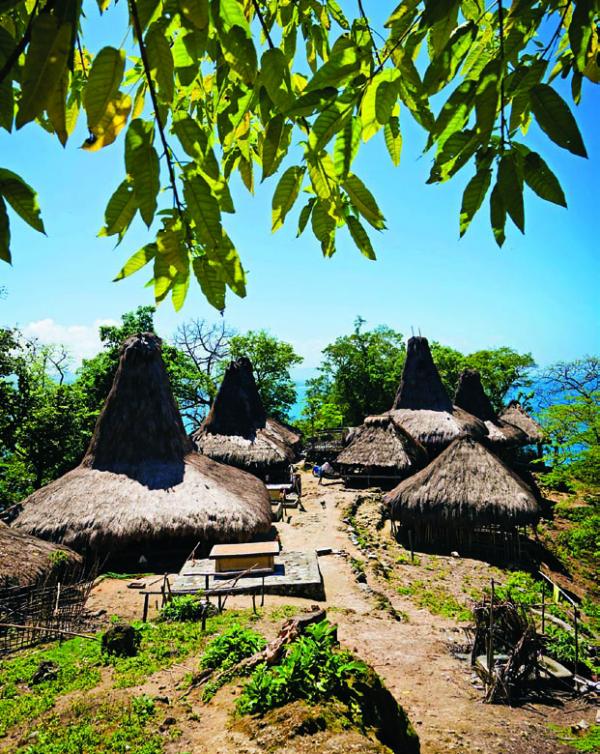

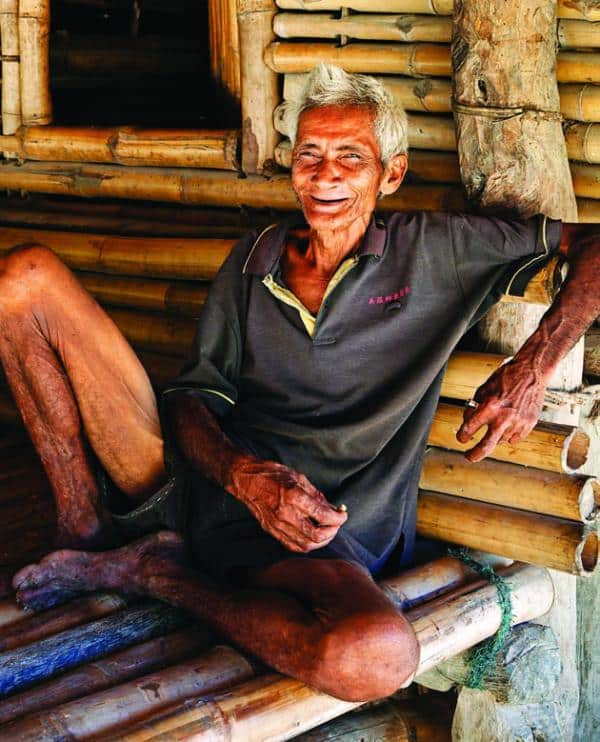

Before we enter his village, Dato sits me down on a rock outside the fortifying walls. There's something he needs to tell me. Dato has worked for Nihiwatu since construction started 18 years ago. A former fistfighting champ, Dato smiles, revealing his missing front teeth. Like most Sumbanese men, he wears a sword in his belt. So, I'm listening.

"Before Nihiwatu came to Sumba," he says, "many, many children were dying in our village. We had no food. Much sickness. Women walk for all day to bring the water."

Villages like Dato's are all built on tops of hills. Great for defense, not so good for bathing. Women are tasked with daily hikes, hours each way, to carry water home for cooking and cleaning. One of the main priorities of the Sumba Foundation has been establishing water sources, wells and pumps. In villages on the parched island, water is a blessing. Dato stands in the narrow stone entryway to his village and demonstrates how it was used to defend against attackers, slashing the air with a not-quite-imaginary sword.

"Please," he says, indicating for me to lead. "You are welcome here."

Dogs bark. Pigs scatter. Roosters crow. I'm nervous about entering, and doubly nervous about going first. Amid the stilted huts, megalithic stone burial sites adorn the village. The Sumbanese are among the last remaining cultures to continue this practice. Their elaborate, animistic funeral proceedings are an archaeological fascination, and photographic documentations are frightfully graphic. Two women are working a traditional loom under a large banyan tree. They wave me over to watch. Other villagers take notice. Children peer out from huts adorned with buffalo skulls and ... are those human scalps? Dato nods yes. Slowly, the village is warming up to me. Children emerge with soccer balls and stick swords. Men offer cigarettes and betel nut. I cringe at their blackened, rotting teeth and politely refuse. They return smiles. If I'm with Dato, I'm with Nihiwatu. And if I'm with Nihiwatu, I am welcome. Dato shows me the water tanks. Old women pump water mere yards from their doorsteps. My back aches as I envision these same women hiking the hillside, careful not to slosh the buckets of water they carried.

He leads me to his home, barely bigger than a treehouse, where he lives with his wife, in-laws and six children. We climb inside and a toddler stokes the central fire. Dato reclines on his bamboo shelf and lights a cigarette. A man at home.

"We keep animals below," he explains. "We live in the middle and make storage above. I was born in this house."

I ask if it's odd to spend his days serving millionaires at the resort and then return to such simplicity. Instead of answering, Dato tells me the story of a girl in his village who became very sick. Nihiwatu sent a car to deliver her to the hospital and then paid her expenses until she recovered.

"She would have died," he says.

Dato's toddler finishes the fire andcrawls into her father's lap. To a child, it is luxury.

"Do you ride a horse?" I ask Dato.

"Of course," he says. "Everyone does."

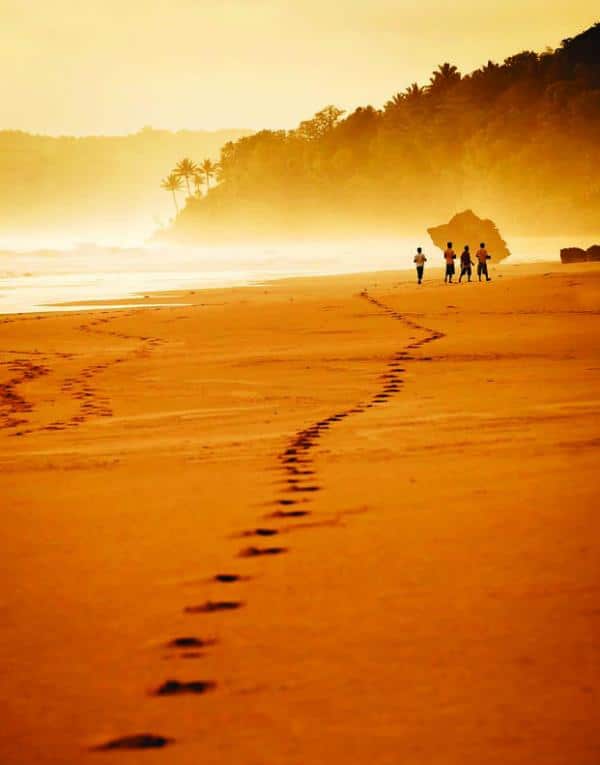

Thundering down the beach. This wild beast. This perfect sand. I'm now vividly aware of Sumba. Before Nihiwatu, I couldn't have found it on Google. These people worship animal spirits. Fertilize their fields with blood. Like the Maasai or the Aborigines, they are a culture that history left behind. And now they're mixing my martini and it isn't even awkward. Here in a place where water buffalo suffice as currency, the butter knife is in exactly the right spot. Pillows are expertly fluffed. Cocktails are cleverly garnished. Claude and Petra teach the resort staff English. Train them in service. And then let them wear their swords to work. Sumba heritage isn't whitewashed. It's celebrated. Maybe it's the 13 bungalows and villas here. Maybe it's the communal dining or the sheer remoteness of it all. But something about this place brings people together. Even the honeymooners take time apart to laugh with new friends.

"Half of these people are return guests," Claude tells me with a mix of humility and pride. "They could afford to stay anywhere in the world, but they keep coming back here. They're also the ones who keep the Foundation running."

Nihiwatu isn't shy about accepting donations. The guests aren't just generous tippers; they're family. It isn't long before you're on a first-name basis with men wearing swords. One holds my hand as we climb the cobblestone stairs after a day of surfing, and it's not strange at all.

"Coming back from fishing today," the Hollywood actor tells me, "one of the boat hands put his head in my lap and took a little nap. People are just more affectionate here."

It's true. I don't feel intrusive asking the bartender how many buffalo he paid for his wife (20) or what he had to do to earn his sword (I can't repeat). I completely understand why people return year after year. Or why someone might try to ride the horses even if they're warned against it. Yeah, they all warned me.

"The local animals are a bit wild," says Claude, trying one last time to convince me. "I keep meaning to bring some tamer ones over from Bali. How about riding the Jet Ski instead?"

When I politely refuse, he asks the stable master, Adi, to walk the horse for me. Walk the horse? Sorry, Adi, but I'm not connecting to Sumba's primal horse culture with you holding the leash. Adi shrugs — the guest is always right — and off I go, forgetting even to ask the horse's name.

We're fine along the mountain trails, skirting ridges and crossing fields of grazing buffalo. We pass through a village and pause for a hilltop vista, then meander down to the beach. But now the horse can see the stable. She senses that we're basically done and, like any minimum-wage employee on a Friday afternoon, she bolts. No amount of whoa -ing or reining can dissuade her from punching out early.

Rattling down the beach, I see Nihiwatu in the distance, barely visible against the breathtaking hillside. Nearby, Nihiwatu 2.0 is taking shape. Three hundred workers are creating the next evolution of Claude's grand vision.

"We're integrating environmental resources that won't be commercially available for five years," he says.

"Stuff that works with the environment instead of against it."

And there it is. With, not against. The key to the Nihiwatu system, to life in this place, and perhaps to surviving this ride. I relax my grip, lean forward on her back and let the horse run free. OK, it's not quite a scene from Snowy River, but I do arrive at the stable in a mostly seated position. Adi is unimpressed. He doesn't hold my hand or put his head in my lap, just leads the horse to graze. Still, I'm feeling good. Accomplished. Alive. I return to the beach on trembling legs. Heart pounding. Sun setting. Then I notice a young boy galloping toward me along the tide line on a striking white pony. His legs are wrapped around the animal's powerful neck; he has just a handful of the pony's mane. Part third-world acrobatics, part equestrian wrestling, and Sumba all the way. I offer a wave as the horse tramples past, and the child risks his grip to return the gesture. His teeth are perfect.