Travel Tales: The Back Road That Ate My SUV

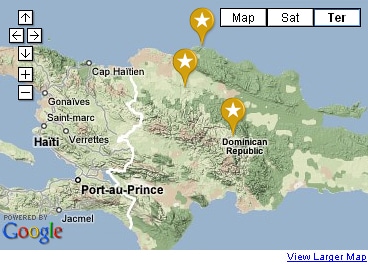

We christen it the Odalismobile, after the man who rents it to us in Luperón , a dusty fishing village where we're staying on the north coast of the Dominican Republic. Odalis takes only one form of payment (cash), offers no damage or theft insurance (unless you count the Club under the front seat of one of his rentals or the holstered .45 under the seat of another; we decline those), and he specializes in the vehicular equivalent of horses ridden hard and put away wet. But if you want to explore the back roads, he's the only game in town.

So we hand over a greasy mittful of pesos and drive off in the Odalismobile, an overused SUV with five balding tires, for a week of venturing off the island's beaten tourist paths — my husband, Steve, behind the wheel and me riding shotgun.

When you ask a Dominican if a certain road will take you where you want to go, he looks at your tires for a while before answering — maybe even kicks them — and eyeballs the height of your vehicle off the ground. Away from the island's main highway, the roads in the Dominican Republic can be awe-inspiringly bad: steep uphills, steeper downhills, occasional washouts, the odd landslide and deep, deep rental-swallowing ruts punctuated by tire-slashing rocks. The fact that many roads are unpaved is a given.

We head into the island's interior, where the scenery is almost painfully beautiful and the roads merely painful. Our first stop: a traditional cassava-bread bakery called Casabe Doña Mechi near Moncíon. Dominicans love their cassava bread, a bland, crackerlike flatbread made from the starchy root of the yucca plant. To the uninitiated, it bears a textural resemblance to cheap cardboard. Still, we are determined to try it straight from the source, and we load up on not just the big, round flatbreads, which are cooked on immense griddles, but also on multiple packages of little cassava-bread curls flavored with anise. They smell yummy as they cook in the bakery's wood-fired ovens, and we are sure they will be delicious.

They aren't. We now have a back seat full of plain and anise-flavored cardboard.

We had heard about a sacred Taino Indian site nearby called Los Charcos de Los Indios — the Pools of the Indians — so we ask Andy, whose family owns the bakery, if he can guide us there. The young man and his father circle the Odalismobile and give its tires and freeboard the requisite once-over. Satisfied, Andy wedges himself into our backseat amidst multiple packages of his family's products, and we head off.

Minutes later, the Odalismobile is perched at the top of a hill. The road down looks like a burro path, crazily steep, all rock and rut, interspersed with craters deep enough to swallow ... uh, an SUV. "No hay problema," says Andy. "No problem," agrees Steve. I just close my eyes and clutch the door handle.

Yes, we make it down — at about one mph — slaloming around boulders and lurching through gullies. And, yes, the jaw-dropping sight of Los Charcos makes me forget (at least temporarily) that the Odalismobile has to make it back up the precipice. An immense pre-Columbian Taino totem, the 100-foot-high face of Los Charcos is carved into a rock wall above a waterfall, its round mouth formed by the opening to a cave. All alone, we soak in the magic of a place Andy tells us few outsiders — save for archaeologists — ever see.

The price we pay for our glimpse of the Taino world is revealed the next day, however, when the Odalismobile's overworked tires start popping like balloons at a kid's birthday party. The first flat comes as we're climbing through paperclip-tight turns on a narrow, shoulderless road leading to the town of Constanza, about 4,000 feet above sea level in the heart of the island's central mountain range. There's not even enough room to pull off, let alone make a repair. We have no choice but to limp along on the rim until we reach a tiny, nameless pueblo consisting of just a few rough houses.

The Odalismobile's doors are barely opened when a swarm of men appears, surrounding the SUV. "Maybe we should go a little farther," I whisper nervously to Steve, taking in the unsmiling faces and remembering we had been warned not to stop — even at police checkpoints — because of the likelihood of a shakedown. "We can't," says Steve, digging out the jack.

That's when the men spring into action, taking matters into their own hands and the jack out of Steve's. Like a well-oiled Indy pit crew, one guy starts jacking up the vehicle, two more unbolt the spare from the rear door and another wedges mountain boulders around the wheels. Yet another stands, lug wrench in hand, ready to remove the flat. Now I realize that their unsmiling faces are serious, not unfriendly: They are clearly accustomed to muchos pinchazos — many flat tires — on their road, and there's work to be done.

Meanwhile, I am offered a chair to join the growing crowd of spectators — women, children, babies and a few males who aren't helping — who watch the proceedings from the sidelines like fans at a sporting event. The Odalismobile is the afternoon's entertainment here (wherever "here" is), but the action is over very quickly. Within minutes, this mountain pit crew has the fresh tire on, the flat back on the door, and the tools stowed. They dust off their hands and wave us on our way.

"Gracias, muchísimas gracias," I thank them profusely, feeling guilty for my initial mistrust. I say we want to reimburse them for their time and trouble. They vigorously wave off my offer of payment, with many "de nadas" — "it's nothing, it's nothing, you're welcome, you're welcome" — but we can't leave without somehow expressing our thanks.

Suddenly I remember the unloved cassava bread and curls in the backseat. I pile them in my arms and hand them to one of the pit crew. "Perhaps your children might enjoy these," I say.

As we rumble back onto the road, leaving behind a cloud of dust, I turn around to wave adiós and see an entire mountain village, adults and kids alike, munching contentedly on cassava curls.

Ann Vanderhoof, author of An Embarrassment of Mangoes, is now sailing the Caribbean with Steve.