New Rides: Surfing In Hainan

One moment a farmer leads a water buffalo to a field, then I blink and five gleaming-white high-rise hotels appear. Brendan and I are on the decidedly modern Hainan Eastern Expressway, headed north to Riyuewan (translated "Sun and Moon Bay") to do something I wondered if I'd ever do in China: surf with locals. The freeway's path up the eastern coastline exposes old and new Hainan. Tiny agrarian villages with rice paddies and rows of taro give way to hotels under construction. Most have billboards with oddly translated English tag lines like "Grasp your ultimate dreams of water and sun at Crystal Ocean Pointe." I can't help but laugh.

"There was an announcement recently that it's a national priority for Hainan to become an international tourism island," says Brendan, explaining the building boom. "The central government in Beijing is focusing a lot on Hainan right now." The small village of Riyuewan, however, has seen little development. There's only one hotel, which caters to busloads of Chinese tourists on carefully scripted tours of Hainan. Twice a day, like clockwork, large tour buses deposit hundreds of tourists in the village. Nearly all are clad in aloha print tops and shorts as they visit a small museum and watch a staged ceremony to bless the local fishing fleet. Heck, for all I know, surfer-watching may even be on the itinerary now. They're ogling their own homeland. It's a novelty to them.

Photo by: Alison Wright

As we enter town, I recognize the noodle and fruit stands and souvenir shops on the main drag. "When the buses leave, Riyuewan becomes a ghost town," says Brendan, reminding me of how these workers return to their villages nestled in the hills after each show. Sun and Moon Bay itself is a wide, sweeping crescent of sand that gives way to those hills. It embodies the "Hawaii of China" comparisons. Last time I was here I was virtually alone, drawn to the machinelike perfection of a peeling wave. So I'm taken aback by what I see in the water. There are at least 15 surfers out.

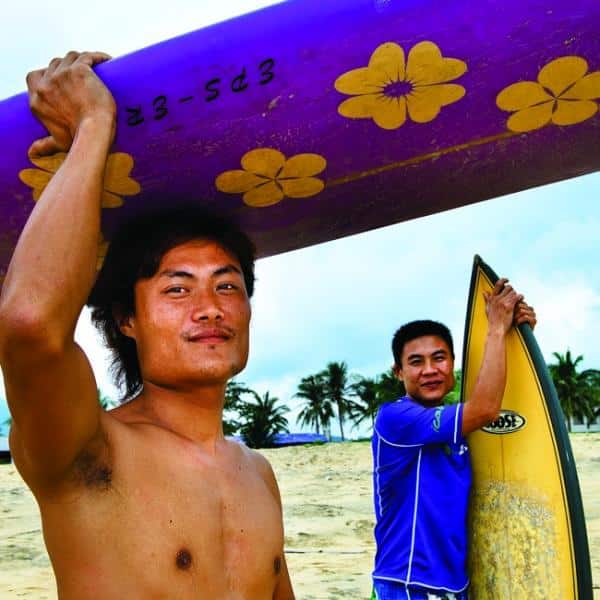

We stop in at Mama's Restaurant, a ramshackle open-air eatery, home to Mama and her two sons, Huang Ning, 37, and Huang Wen, 26, Riyuewan's first local surfers. Though I speak no Chinese, and my last visit was a while ago, they welcome me as family. Even Mama jogs over for a hug. "Now there are surfers all the time here," Huang Ning tells me through a translator. The brothers are happy for the new business. Mama's now rents boards in addition to serving fresh seafood.

Photo by: Mark Anders

The brothers surf with us for the next week as a steady stream of local and visiting surfers come and go. Unlike in my first visit, the shopkeepers in Riyuewan don't look at me like an alien. They smile and nod as I buy bananas or enjoy a bowl of noodles. They know I surf and seem pleased that I'm here. One afternoon at Mama's, a Riyuewan local — a fireplug of a guy in his late 20s with a mop of black hair — walks over to me as I survey the waves. "You take me surf?" he asks with a big toothy grin. I smile back. He speaks to me in Chinese. "He says he remembers you from your last visit," translates a friend. "He's a local diver, a fisherman. You lent him your paddle board for his dive mask." Though he speaks precious little English, that afternoon I use gestures and diagrams in the sand to teach him surfing. Before long, I have him standing up and riding in the soupy waves near shore. The diver's beaming smile says it all. He, like other locals around us, is hooked.