Italy's Secret Ingredient

Antonio the Sailor insists I join him for appetizers on his rooftop patio overlooking centuries-old facades on the Mediterranean island of Procida. By the look of his flowing locks and soft hands, and his spread of veil-thin bresaola and fist-size mozzarella, Antonio is not your typical coarse sailor.

I follow the sailor past the table and enter his garden, thick with beanstalks, tomato plants and hedges of oregano. He muscles into the impossible thicket and carefully gathers a bouquet of mint. He must have something special in mind.

"Special" is why I'm here. Tomorrow I'll set sail into the Phlegrean Archipelago, a scatter of islands off Italy's west coast, where the purest Italian foods are said to be found. That's the promise from Peggy Markel, my gourmet guide to the little-known isles of Procida, Ventotene, Ischia and Capri. But Peggy insists that the journey start here, on a rooftop with Antonio.

"Out here, in the middle of nowhere," Peggy says, "they have better Italian food than anywhere in New York City."

And why is that? Do they have a forgotten technique for curing meat or growing herbs? Speaking of that, here comes Antonio with what might be a hint of the secrets to come. The sailor hands me a glass. "Mojito?"

He has served me rum with mint, smashed into sugar and ice. This is an old-country recipe?

"No Bellini? No amaretto?" I blurt out, wondering about the promised authenticity.

"Real Italian, you say?" Antonio says, savoring a lump of his mozzarella. "It isn't only about what you eat, but how you eat it and who you eat it with. Peggy will show you."

Twelve hours later, I'm surfing the blustery bow of a Hanse 540e sailboat as we crackle westward toward Ventotene. It's a long crossing, 26 nautical miles, so our plan is to drop sail for lunch halfway. But with gusts snapping us along, our skipper, "Tony Tony" Scotto di Perta, fires us into the Ventotene port almost two hours early. "OK," says Tony Tony. "Now we eat."

Ventotene is an austere place of black volcanic rock and tall grasses the color of olive oil. The chirpy pastel-splashed town has attracted a tiny Italian-only contingent of tourists for the summer. The rest of the year, the place will be as empty as the abandoned ruins that speckle its shores. We encounter the first of these relics as soon as we wobble off the boat. Seamen and vendors operate from arched caves that were chipped from the black tuff for storage two millennia ago.

The first merchant we meet, an older gentleman with skin parched the color of rare beef by decades in the sun, is selling jars of preserved produce picked from his farm. He introduces himself as Vincenzo Taliercio, and tells me the changing European Community food regulations are making it difficult for him to continue his food trade. Last year, local administrators issued Vincenzo an ultimatum: Create official labels with ingredient lists, or stop selling. He made the shift, but his brother went out of business. As I listen to this story, I pick up jar after jar and scan for some ubiquitous ingredient — the secret to the food here, I hope — and find nothing but wild thyme, basil, pepperoncini and other predictable contents.

"I have a passion for food," Vincenzo says as I turn back to him. "But I don't know how much longer I can stay ahead."

I've heard similar stories from Peggy — centuries-old markets shutting down, chefs taking family recipes to the grave, food traditions being lost. In a time when "Italian" has come to mean Mario Batali and Olive Garden, the nuanced flavors of places like Ventotene have become harder and harder to find.

"Discovering and safeguarding food culture is as important as digging up relics," Peggy says. "It's more than anthropology. By sharing food and breaking bread, we create relationships."

It also tastes good. Taliercio's anchovy- and caper-stuffed peppers burst in my mouth, and the hard goat cheese soaked in chili oil is so amazing that I can't resist loading up on jars.

We continue along the Ventotene waterfront to Ristorante Bar da Benito. The place smacks of old Italy: a covered terrace that overlooks a placid bay once used for Roman fish pools.

On the terrace, we find 84-year-old Benito Malingiere, with a bushy head of milk-white hair and a silver anchor around his neck, working in his outdoor kitchen. He's basting fish and clams with a switch of rosemary over an open grill, a method that's been handed down through several generations. He wipes his hands and introduces himself as King of the Amberjack. He then lays out a platter of grilled seafood so succulent that it might as well still be swimming.

After the bones are picked clean, Benito, who by this point has given up the formality of a glass and is drinking white directly from a carafe, begins serenading the restaurant with Neapolitan love songs. He pays special attention to four svelte 20-something Roman girls at the table next to ours, and they start to croon the choruses with him. Hours later, as the girls spill out of the restaurant, I stop one of them.

"You've been here before?" I ask.

"We come every year," she tells me, before dropping a clue. "We have good food in Rome, but we don't have Benito."

Apparently, even comely Italians want to cut carbs to shed pounds. Like our captain, Tony Tony. So in a still bay, Peggy cooks up a freshly caught octopus and slices it into a salad of fennel, lemon and potatoes — a local delicacy that's relatively easy on starch. After my hour of leaping off the boat deck into the warm Med and kicking after schools of iridescent fish, the food tastes ambrosial to me. Antonio the Sailor's parting words ring in my head — perhaps the most important link to Italian food is your company and your surroundings. It's hard to imagine this unpretentious seafood salad tasting as good at the finest restaurant back home.

This languid meal, together with the hours lolling in the sun, mark the trip's turning point. Before anchoring here, my mind was still preoccupied with the pace of work and home. But in this quiet cove, all that recedes. "It's elemental, just like the food," says Peggy. "Moving at will from island to island is the best way to appreciate this place."

Perhaps it's the satisfying midday meal or the sea breeze or the effect of all the empty wine bottles, but there's a newfound sense that even if we never left this spot, the trip would be perfect. Of course, we do move on, ticking and tacking eastward on light winds toward mountainous Ischia.

Once we've moored at Ischia's Casamicciola Terme, we wend our way up the flank of 2,500-foot Mount Epomeo to La Trattoria Il Focolare, a family-run country eatery. Riccardo d'Ambra, the 66-year-old patriarch and head of Slow Food Ischia and Procida, launches into what will be an hours-long evening of wine and feasting and culinary discourse. "This may look like just a restaurant," Riccardo says in a grandiose opening statement, "but it's a living slice of this island's history."

The starting point for it all is Il Focolare's specialty: rabbit.

Having likely arrived on Ischia with the Phoenicians, rabbits became both a local delicacy and a vineyard-pillaging pest. To control the problem while keeping them for their meat, the Ischiatani invented a unique method of raising the animals underground where they wouldn't cause problems. The practice died out as industrial rabbit farms took over, but Riccardo has revived the tradition to supply Il Focolare with its most popular dish. Riccardo takes us up the steep vineyards behind the restaurant. There he plucks wild thyme while his daughter, Silvia, lures a rabbit from the tunnels for us to see.

"It's not about the rabbit," Riccardo says. "We're saving our traditions." I'd even go as far as to say that the rabbit on my plate derives its flavor more from Riccardo's underground stories than from anything else. Maybe the key to these islands' cuisine is something immeasurable and unstirable.

From the farm we walk back to the restaurant to meet Riccardo's two oldest sons, Agostino and Francesco, who run the kitchen. Agostino worked a stint at New York City's beloved Italian eatery Cipriani, but was disillusioned and returned to the family business. "They asked me how my chicken parmesan was," he remembers, shaking his head. "We make parmigiana di melanzane — eggplant, not chicken. Seventy percent of what is passed off as Italian is an amalgamation or an illusion."

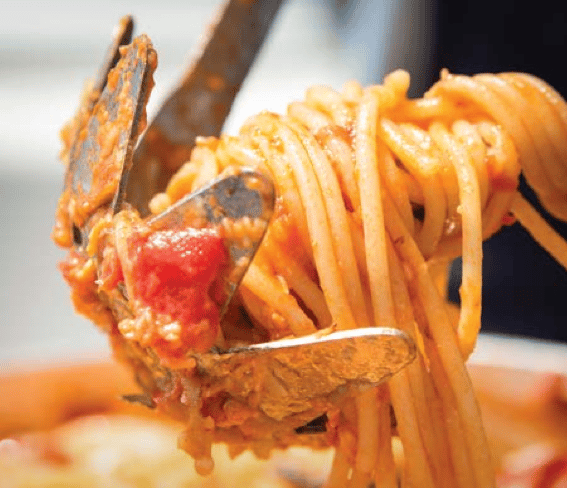

Agostino demonstrates how to prepare coniglia Ischiatana, braising the rabbit in white wine and then stewing it in a clay pot with garlic, cherry tomatoes and the thyme that Riccardo just picked in the fields. Then he shepherds us to a table and sends out platter after overflowing platter of food, from antipasti to myriad pastas and, finally, the marquee rabbit.

"We aren't afraid of becoming modern," Riccardo says as the plates gradually pile up on our table. "We just don't want to lose our past — our identity — in doing it."

We sleep late the next morning, and after breakfast we hoist the sails and run eastward to Capri. The Monte Carlo of the Phlegrean, this glittering island is a magnet for moneyed Europeans in pastel-hued linen and rhinestone-studded bikinis. Tony Tony drops anchor in the Bay of Naples, where our boat looks like a toy anchored among 200-foot yachts. It's the stuff of Bond super-villains, and this strikes me as an unlikely place to shop for deeply Italian ingredients. Peggy admits she's found the culinary side of Capri challenging, but she urges a look anyway.

At 50, Peggy is curious and confident enough to approach anyone. She collects friends with the ease with which most people collect recipes. When we stop for espresso and pastries, she excuses herself. Fifteen minutes later she's back with a lead.

Within the hour, we're in the kitchen at Villa Verde, one of Capri's top Italian restaurants, with owner Franco Limbo. He shows us the sea bass and prawns he's just bought from he fishmonger and demonstrates how to stuff fiori di zucchine, the squash blossoms he picked this morning from his garden. Then he insists we stay for lunch and sends a huge sampler dish to our table. There's ravioli filled with mozzarella, caprese salad, pizza with olive oil, and the zucchini blossoms. The food is perhaps the most delicious of the trip so far.

"This is simple food, but you can't have it anywhere else," he says. "It's a taste of our earth here on Capri."

It's true. The tomatoes in the caprese explode with the sweetness of the sun. The zucchini flowers taste delicate. And yes, in the marinara I can almost taste the minerals from the soil. Capri might be flashy, but the food is as pure as the land.

Still, I can't resist teasing Limbo about the pizza, the ultimate Italian cliche. He's unapologetic. "Pizza, pasta, pizza, pasta, pizza, pasta," he asserts, gesticulating with his hands from side to side. "If you can't make a good pizza or pasta ... fahgettaboudit!" He says it without a hint of irony.

Our boat gusts past limestone islets toward the biggest surprise of the cruise. As we come toward the harbor in Amalfi, Peggy sketches out an itinerary. It revolves around visiting an old friend of hers and his lemon groves.

Citrus? This is the culmination of food in Italy?

And then I see the trees on stair-step terraces carved into the valley's limestone hillsides. They are sagging under the weight of daffodil-hued fruit. The sea breeze is laced with floral hints of citrus. Lemons, it turns out, are the essence of Amalfi. Some of the harvest is exported, but much of it goes to the production of limoncello, a sweet, potent digestif.

I've never had a taste for the stuff, which could be a problem.

We climb into the hills to meet Luigi Aceto at his lemon farm in Valle di Mulini. A self-described anarchist and poet, Luigi is 80 years old but moves like someone 30 years younger. His pate is ruddy from years in the fields and is offset by a wild ruff of white hair. He embraces Peggy and kisses her cheeks and the backs of her hands, then greets each of us with a lingering handshake. He leads us into his groves as he tells us how he started in 1968 with a tiny strip of land and just 10 lemon seedlings. He now has more than 2,000 trees.

"I'm the eighth of 13 children, and of course my parents couldn't make love in front of the family so they had to go to the garden," he begins. He speaks with the passion of a theater performer, gesturing and touching you when he wants to make a point. He clutches my arm. "That's where my love affair with the lemon began, because surely and without a doubt I was conceived under a lemon tree. I'm certain there's lemon jelly, not blood, running through my veins."

Inside a building on his property, Luigi pours a round of limoncello. His passion is infectious because, in spite of my preconceptions, I gladly drink. I'm not sure why, but in this moment I actually love the syrupy concoction. I tell Luigi that I've never liked limoncello before, but that his is fantastic.

"Our lemons are different. They are like little creatures. We provide everything for their well-being," he says, staring into my eyes. "The important thing is that these lemons come from this place. They have clean air and beautiful land in them."

Here at last is the truth, and it isn't at all what I'd imagined. I'd been looking for an ingredient that I could buy or pick. A quick tip on basting or a nuance of mixing. I wanted to find something to take home in a jar or on a piece of paper. But the true flavor of this region comes from strong sunshine, heavy wind and crisp water. And, most important, it's a result of time and patience. That, for me, is tough to swallow, because those are ingredients I rarely choose to afford. Back home, it's all about consistency and convenience. Make it the same. Make it quick.

Not here in the Phlegrean. The lemons are knurled, odd-shaped and individually beautiful. The rabbit recipe has been stewing for centuries. The herbs and vegetables are harvested from the family garden and preserved by hand. And when I sit down to eat with the Italians on these slow islands, by nature we all linger. The food is not rushed, and neither are we.

The coastal climate here can never be taken away, and Peggy says she's optimistic that, in spite of the passing generations and some tighter restrictions on what can be sold in markets, the cultural essence will also remain. "It's a society devoted to food and time and living well," she says.

Antonio the Sailor raises his own food, for instance, and Tony Tony gave up a career to be on the water. Even if the economic crisis gets worse, it seems nothing here will change. People will still grow beautiful tomatoes and pick the best lemons. They'll still be here living a slow, contented life.

As we start to say goodbye to Luigi, Peggy tells him she's cooking spaghetti al limone for lunch. He insists that she use his lemons. Instead of just grabbing some from a basket, he tells us to wait and then sets about collecting fresh ones. With spears of afternoon sunshine glinting through the overstory and the perfume of citrus rising on the Mediterranean breeze, Luigi meanders from tree to tree in search of the most beautiful lemons. He then climbs into high branches to pluck the perfect fruit.