Australia's Most Dangerous Wildlife (And How To Avoid It On Your Vacation)

It's no secret that Australia is home to some of the world's most dangerous animals. There are, for example, some 220 species of snake in the country, and 145 of them are venomous. Its coastal waters are home to a plethora of exotic fauna, with swimmers having to keep a sharp eye out for sharks, jellyfish, the occasional crocodile, and – oh yes — yet more snakes. Spiders proliferate in major population centers, flightless birds have a penchant for karate, kangaroos love to box, and in rock pools, the dreaded blue-ringed octopus flashes its neon warning sign to anyone foolish enough to approach it. Even the seemingly innocuous platypus has a hidden stinger.

All of this is enough to put you off visiting. Which is a shame, because Australia has so much to offer beyond its reputation as a land filled with menacing beasts. Sporting some of the world's most scenic vistas, world-class island and coastal getaways, and an entire menagerie of incredible creatures that really aren't trying to kill you, a visit to Australia is an adventure.

Yes, certain sharks are dangerous, but you'll probably never encounter one. Some of the spiders are fearsome to behold, but nobody in Australia has died from a spider bite since 1979. Snakes are abundant, but most of the time just want to be left alone. According to a report commissioned by NCIS (pdf), between 2001 and 2017, there were 541 animal-related deaths. The main culprits? Horses, bovines, and dogs. All and all, death by critter is unlikely; however, you'd still do well to steer clear of some of the country's more perilous wildlife.

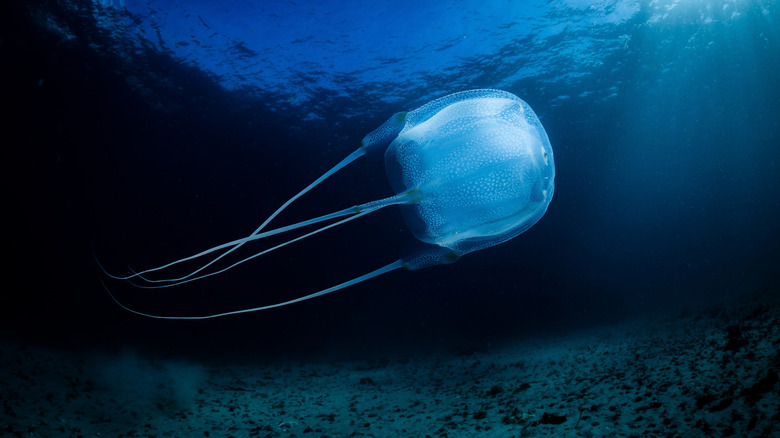

Box jellyfish

Somewhere around one thousand species of jellyfish inhabit the coastal waters around Australia, and over one hundred of these are found drifting in or around the islands and attractions of the Great Barrier Reef. They have no brain or heart, predate the dinosaurs, are made of up to 98% water, and possess no defense mechanisms other than the their well-known sting. While most jellyfish stings are nothing to write home about, in Australia, there are three to watch out for: the blue stinger, Irukandji, and the much-dreaded box jellyfish.

While jellyfish often drift on currents, they can actually swim. The box variety stands out, at least in part, due to its eyes (it has 24 of them), which it uses to hunt down prey. Their sting is as painful as it is unpredictable. Some symptoms are immediate, while others might arise hours after envenomation and include abdominal and chest pain, spasms, nausea, and, in very rare cases, cardiac arrest. In Australia – with its sophisticated medical services, the box jellyfish only kills someone once every three to four years (via Barrier Reef Australia). If you suspect a box jellyfish sting, call 000 — the Australian equivalent of 911 — at once.

Avoiding box jellyfish mostly centers on staying aware of your surroundings and paying attention to environmental factors. What the locals refer to as "stinger season" varies from location to location, but generally falls between the months of October and May. Regardless, it's a good rule to always swim between the flags when enjoying an Australian beach, as they indicate that a lifeguard (likely trained to deal with stings) is present.

Kangaroos

Few animals are more synonymous with a specific location than the kangaroo; these oversized marsupials are living Australian mascots. There are only four species: red, eastern gray, western gray, and the antilopine kangaroo. Of these, the red is by far the most dangerous. Of course, the concept of danger is a relative one in Australia. To start, most kangaroo-related deaths are road accidents. And while collisions are certainly common enough, casualties resulting from them are vanishingly small. Per the Kangaroo Management Taskforce (pdf), there are over 7,000 insurance claims against collisions with kangaroos in the country every year, though these creatures caused only 18 total Australian fatalities between 2000 and 2010.

Elsewhere, kangaroos will attack only if they feel threatened. A photo opportunity with a cute quokka on Rottnest Island is one thing; a selfie with a kangaroo is quite another. A male red clocks in at almost 6 feet tall and can weigh as much as 200 pounds; approaching one in an upright position may make it think you intend to spar. This is something you really don't want to do since its kick can be deadly.

Keeping yourself safe from kangaroos is all about adopting a common-sense approach. Many Australian cars are equipped with a type of bull bar known as a roo bar; if renting a car for some rural exploration, it's a good idea to choose a vehicle with one already fitted. Meanwhile, avoiding a decidedly one-sided boxing match with a kangaroo couldn't be easier. Simply don't approach them. Kangaroos like to do their own thing, and when treated with the respect that wild animals deserve, the worst that is likely to happen is that they will hop off out of view.

Sydney funnel-web spiders

A fear of spiders is one of the most common phobias in the world, and in the case of the Sydney funnel-web, that fear might well be justified. Most spiders are venomous, but that fact is somewhat mitigated by a couple of caveats: first, for the most part, their venom has no effect on something as large as a human. Second, in many cases, their fangs aren't large or forceful enough to penetrate skin. Sadly, neither of these things is true of Sydney's most infamous arachnid.

Many different species of funnel-web spiders are common on the east coast of Australia as far south as Tasmania and as far north as the upper half of Queensland. They are, however, less well known than their New South Wales brethren due to the fact that they are relatively harmless and rarely encountered. The Sydney funnel-web, on the other hand, lives in Sydney — and some of its surrounding cities – and it is this intersection of a human population of several million people with a spider that likes to hide in small, dark spaces that makes it so dangerous.

Most medically serious bites involve an encounter with the male of the species, but it's important to note that there hasn't been a single fatality since the introduction of the antivenom in 1981, according to the University of Melbourne. If bitten, dial 000 and wait for medical respondents to arrive. Avoiding the spider primarily consists of keeping a sharp eye out. Locals keep their gardens free of detritus to discourage the spider from making burrows. Indoors, it's a good idea to check your shoes before putting them on.

Sharks

Despite its status as the smallest continent, Australia is a sizeable place made up of some 2,969,976 square miles. And with over 21,000 miles of coastline, it's little wonder that encounters with sharks are common.Thankfully, most sharks aren't all that dangerous. For example, running into a reef shark while scuba diving on the barrier reef is nothing to worry about; they don't see you as food, and if you leave them alone, they will pay you the same courtesy. Other species, such as the gray whaler and leopard shark, typically tolerate the presence of human swimmers without incident.

That said, some sharks really are dangerous. As humpback whales migrate along the coast, great white sharks follow. Other species, like the bull and tiger shark, are also best avoided. In 2023, Australia recorded no fewer than 15 unprovoked shark attacks, which included four fatalities — three from a great whites and one from a bull shark, per the International Shark Attack File. The gorgeous Byron Bay boasts the most shark attacks in Australia. The low chance of an encounter with one of these larger predators does not detract from the seriousness of such instances. Spotter planes fly over beaches at certain times of the year armed with a siren to warn bathers away. Making sure you swim between red and yellow flags is a good practice, since it means that a lifeguard equipped with binoculars is present; if you hear continuous and rapid whistle blasts, it means it's time to exit the water.

Blue-ringed octopuses

The scourge of tidal pool waders, these tiny yet distinctive octopuses rarely bite, but when they do, it can be a life-threatening event. The good news is that the beautiful molluscs let you know when they feel threatened via vivid blue rings that appear all over their body. Still, these creatures are hard to spot. Adults measure about 4 to 5 inches long, and, aside from the blue rings, they are well-camouflaged. The venom they produce is tetrodotoxin -– the same substance found in puffer fish –- and is said to be around 1,000 times more toxic than cyanide. Only three deaths have occurred since the 1960s from a blue-ringed octopus' bite, two of which were in Australia, per the Australian Institute of Marine Science. A woman who was bitten in 2023 survived the ordeal.

As with most of the animals on this list, blue-ringed octopuses just want to be left alone. When wading in shallow rock pools, wear thick-soled shoes. Australia is also not the best place to pick up shells; these tiny creatures like to hide inside them and may fall out and bite you if startled. Keeping a respectful distance is well-advised, as is recalling that the tell-tale blue rings are not always visible; assuming that any small octopus you encounter is dangerous is good practice.

Snakes

A full 65% of the snakes you can encounter in Australia are venomous, and, in a world where the global average of venomous to non-venomous snakes stands at 15%, that's an impressive figure.Some 3,000 snake bites occur every year, but fatalities are rare, averaging about only two per annum (via a 2021 study published in Toxins). Half of all the recorded deaths since 2,000 took place in or around a person's home, and a full fifth were a consequence of an attempt to handle or kill the snake, per a 2017 study included in Toxicon.

The eastern brown is the most dangerous species of snake in Australia. Responsible for about 60% of snake bite fatalities, its fearsome reputation stems from two main factors. First, like the funnel-web spider, it often lives in close proximity to humans and is particularly at home in semi-urban and farmed locations. Second, it's fast; the eastern brown can hit speeds of 12 mph, but is unlikely to chase anyone or anything unless provoked. However, it is not the most problematic snake in Australia – that distinction belongs to the inland taipan, which just so happens to be the most venomous snake in the world. But it's also one that isn't often encountered; found mostly in remote areas of Queensland, it rarely ventures above ground and is both shy and unassuming. Few people have ever been bitten by one, and all have lived to tell the tale. Additionally, in the beautiful waters surrounding Australia, sea snakes proliferate, yet these too rarely bite.

Avoiding contact with such creatures is part of life in Australia; yards are kept clear of debris and long grass, and appropriate footwear is worn when walking in the bush. Meanwhile, a general assumption that every snake you see is venomous creates a sense of caution that helps maintain a polite distance from slithering fauna.

Saltwater crocodiles

People from North America are at least somewhat familiar with the concept of large carnivorous reptiles living near their locale, but the saltwater crocodile is no alligator. Found in coastal waters, reefs, and brackish inland waterways across Australia (including one of the world's most dangerous national parks), these salties — as the locals call them — can grow to 23 feet in length and weigh over 2,000 pounds. They are the largest living reptile in the world and as close as you'll ever come to an encounter with a carnivorous dinosaur. Territorial by nature, these large predators sometimes attack humans and are responsible for around two deaths every year in Australia, as reported by The Sydney Morning Herald; in 2014, four fatal attacks occurred. Females are much smaller and less aggressive than the males, yet remain dangerous.

The best defense against a crocodile attack is twofold. First, have a clear idea of their habitat — they swim out to sea but are ambush predators, and attacks on divers are exceedingly rare. Encounters are more likely to take place near inland waterways, and warning signs are generally on display at these locations. Second, Queensland Government advises being mindful of your surroundings. In areas where crocodiles are known to frequent, it's best to stay at least five yards away from the water's edge and dispose of food scraps safely, as crocs have a keen sense of smell and are not above scavenging. In such spaces, small boats are a no-no, and pets should be kept on leads and well away from the water.

Stonefish

To be clear, there have been no recorded deaths from a stonefish sting in Australia, a country that may be better equipped to deal with dangerous critters than some of the other places this highly-toxic marine animal might be found, such as Fiji, which has its own list of potentially hazardous creatures to stay away from. The threat they pose to humans mainly stems from two things; first, as the name suggests, the fish is expertly camouflaged as a stone or rock. Second, although not lethal — thanks to the existence of an antivenom — stepping on a stonefish is likely to seriously ruin your holiday. The sting is excruciatingly painful, and recipients may require hospitalization for a couple of days or longer, depending on how much venom they receive.

Avoidance is the best remedy here. As is always the case when swimming in Australia, stay between the red and yellow flags. Such flags indicate the presence of a lifeguard. Medically trained, their first aid kit includes items such as vinegar for jellyfish stings and hot water for stonefish envenomation. Such measures are necessarily interim; dialling 000 will alert emergency services, which can administer an antivenom upon arrival. As an added precaution, refrain from picking up or standing on stones while walking on the beach; the stonefish's gift for camouflage should not be underestimated. No matter how convinced you are that you aren't looking at a living thing, the best policy is to leave any and all forms of beach decoration well alone.

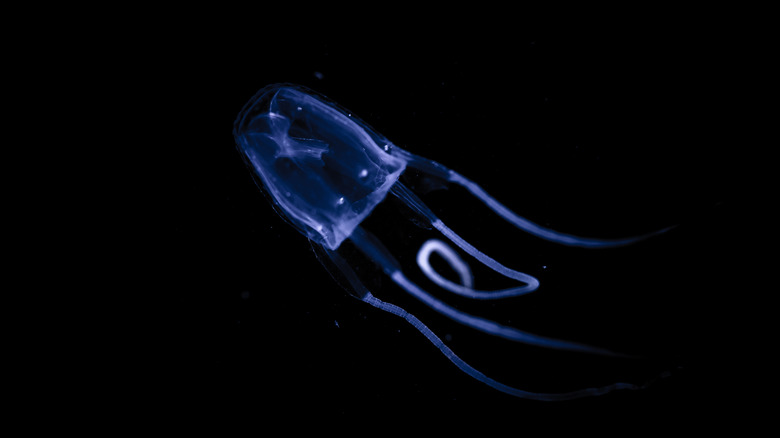

Irukandji jellyfish

Though not the most dangerous jellyfish in Australia, the Irukandji's sting is so potent that the symptoms it provokes have their own medical term – a condition known as Irukandji syndrome. Despite being related to the box jellyfish, the Irukandji is much smaller, measuring around 0.75 inches across (give or take). This, coupled with the fact that they are almost completely transparent, means that spotting one in the ocean is virtually impossible.

An Irukandji sting is initially mild, but soon progresses, with the principal risk to life arising from cardiovascular failure. Medical aid should be sought at once by dialing 000. The good news is that these jellyfish prefer the deep ocean and occasionally drift into coastal waters. When they do, they approach from the north towards the sparsely populated regions of the island continent. As a consequence, since 1883, there have only been two recorded fatalities, according to Phys.org. To further up your chances of avoiding a sting, only swim in designated areas and consider wearing a stinger suit between October and May.

Cone snails

When you think of dangerous animals, your mind may turn to a few common tropes: snakes, sharks, the occasional predatory cat, perhaps? Rarely does one worry about anything as seemingly innocuous as a snail. To be fair, there has only ever been one recorded death from a cone snail, and that was in 1935, per Queensland Museum. Still, the lethality of this predatory mollusk was brought into sharp focus in 2021 after a teenager shared that they had picked up a live cone snail and was lucky to escape with their life.

The cone snail uses its venom to paralyze its prey so that it can eat them at its leisure; sadly, for humans, it carries enough venom to potentially kill 700 people. With no antivenom available, those unfortunate enough to receive a sting are at serious risk of respiratory paralysis and may need prolonged CPR. Once again, the best defense against a cone snail is to practice restraint when enjoying Australian beaches. That pretty shell you spot lying in the sand might look like a tempting souvenir, but it's best left alone.

Redback spiders

If the Sydney funnel-web is the stuff of an arachnophobe's nightmares, the redback is more of a daytime fever dream. This spider – closely related to the black widow spider of North American fame — is found throughout Australia. Easily identifiable by its red stripe, bites are common due in part to the spider's love of urban areas.The pain from the bite is severe, and the rapid onset of symptoms include palpitations, nausea, and vomiting. If bitten, apply ice — not pressure — and wait to see if symptoms progress. Thankfully, it's not all unwelcome news.

To start with, only the females bite, and males don't spin webs; a female redback sitting in its web is easier to spot, so, there's that. Secondly, their fangs are quite small, so although a bite is a definite risk, envenomation does not always occur. Over 250 cases receive antivenom annually in Australia, though it is suspected that many of the milder bites go unreported, per Australian Museum. In such instances, the failure of the spider to deliver enough toxin to make anyone seriously ill is a blessing. Still if in doubt, or if symptoms are progressing, dialing 000 or seeking out the nearest hospital is probably a good idea.